Do Families in Japan Have Access to Electricity

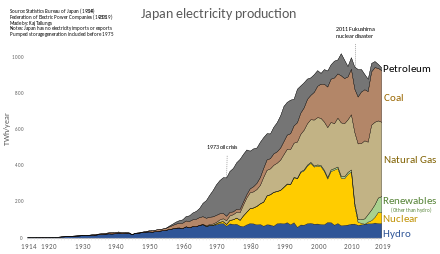

Electricity product in Nihon by source.

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Production (2014) | 995.26 TWh |

| Share of renewable energy | 9.7% (2009) |

The electric power industry in Nippon covers the generation, transmission, distribution, and sale of electric free energy in Japan. Japan consumed 995.26 TWh of electricity in 2014.[i] Earlier the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, most i third of electricity in the country was generated by nuclear power. In the following years, nearly nuclear power plants have been on concord, existence replaced mostly by coal and natural gas. Solar power is a growing source of electricity, and Japan has the third largest solar PV installed capacity with about 50 GW every bit of 2017.

Nihon has the second largest pumped-hydro storage installed capacity in the world later Communist china.

The electrical grid in Nippon is isolated, with no international connections, and consists of four wide area synchronous grids. Unusually the Eastern and Western grids run at different frequencies (50 and 60 Hz respectively) and are connected past HVDC connections. This considerably limits the amount of electricity that can be transmitted between the north and south of the country.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War and the succeeding Pacific War, the entirety of Japan'southward electricity sector was state-owned; the organisation at the fourth dimension consisted of a Japan Electrical Generation and Manual Visitor ( 日本発送電株式会社 , Japan Hassōden kabushiki gaisha , otherwise known as Japan Hassōden KK or Nippatsu) and several electricity distributors. At the behest of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, Nippon Hassōden became the Electric Power Development Co., Limited in the fifties; and virtually all of the electricity sector that are not under the command by EPDC was privatized into ix government-granted monopolies. The Ryukyu Islands electricity provider was, during the USCAR era, publicly owned; information technology was privatized presently after the islands' access into Nippon.

Consumption [edit]

| | This commodity needs to be updated. (Jan 2018) |

In 2008, Japan consumed an average of 8507 kWh/person of electricity. That was 115% of the EU15 average of 7409 kWh/person and 95% of the OECD average of 8991 kWh/person.[ii]

| Apply | Product | Import | Imp. % | Fossil | Nuclear | Nuc. % | Other RE | Bio+waste matter* | Air current | Non RE use* | RE % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | viii,459 | 8,459 | 0 | 5,257 | 2,212 | 26.i% | 844 | 146 | 7,469 | 11.seven% | ||

| 2005 | 8,633 | eight,633 | 0 | 5,378 | 2,387 | 27.6% | 715 | 153 | 7,765 | x.one% | ||

| 2006 | ix,042 | ix,042 | 0 | 6,105 | 2,066 | 22.8% | 716 | 154 | 8,171 | 9.half-dozen% | ||

| 2008 | eight,507 | 8,507 | 0 | 5,669 | 2 010 | 23.6% | 682 | 147 | seven,679 | 9.vii% | ||

| 2009 | 8,169 | 8,169 | 0 | 5,178 | 2,198 | 26.9% | 637* | 128 | 27* | 7,377 | 9.7% | |

| * Other RE is waterpower, solar and geothermal electricity and air current power until 2008 * Non RE use = employ – product of renewable electricity * RE % = (production of RE / use) * 100% Annotation: European Union calculates the share of renewable energies in gross electrical consumption. | ||||||||||||

Compared with other nations, electricity in Nihon is relatively expensive.[3]

Liberalization of the electricity market [edit]

Since the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, and the subsequent large calibration shutdown on the nuclear power manufacture, Japan's 10 regional electricity operators have been making very large financial losses, larger than Usa$15 billion in both 2012 and 2013.[4]

Since and so steps have been made to liberalize the electricity supply market.[4] [5] In April 2016 domestic and small business mains voltage customers became able to select from over 250 supplier companies competitively selling electricity, though many of these only sell locally mainly in large cities. Besides wholesale electricity trading on the Japan Electrical Power Commutation (JEPX), which previously simply traded one.5% of power generation, was encouraged.[half dozen] [7] By June 2016 more than than 1 million consumers had changed supplier.[8] Nonetheless full costs of liberalization to that indicate were around ¥eighty billion, so information technology is unclear if consumers had benefited financially.[8] [9]

In 2020 manual and distribution infrastructure access will exist made more open up, which volition assistance competitive suppliers cut costs.[8]

Transmission [edit]

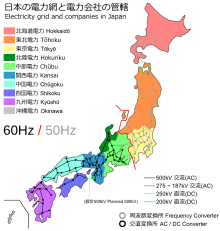

Map of Nihon's electricity transmission network, showing differing systems between regions

Electricity transmission in Japan is unusual because the country is divided for historical reasons into 2 regions each running at a different mains frequency.[10] Eastern Nippon has fifty Hz networks while western Japan has sixty Hz networks.[10] [11] Limitations of conversion capacity causes a clogging to transfer electricity and shift imbalances between the networks.[10] [11]

Eastern Japan (consisting of Hokkaido, Tohoku, Kanto, and eastern parts of Chubu) runs at l Hz; Western Japan (including about of Chubu, Kansai, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Kyushu) runs at threescore Hz.[10] [12] This originates from the kickoff purchases of generators from AEG for Tokyo in 1895 and from General Electrical for Osaka in 1896.[xiii] [14]

This frequency difference partitions Japan'due south national grid, so that power tin can only exist moved between the two parts of the grid using frequency converters, or HVDC transmission lines. The purlieus between the 2 regions contains four dorsum-to-back HVDC substations which convert the frequency; these are Shin Shinano, Sakuma Dam, Minami-Fukumitsu, and the Higashi-Shimizu Frequency Converter.[ citation needed ] The full transmission chapters between the two grids is 1.2 GW.[15]

The limitations of these links have been a major problem in providing ability to the areas of Japan affected by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.[xiii] During the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, there were blackouts in some areas of the state due to bereft power of the three HVDC converter stations to transfer energy between the 2 networks.[12]

A few projects are underway to increase the electricity transfer betwixt the fifty Hz (eastern Nippon) and 60 Hz networks (western Japan) which volition improve power reliability in Japan.[11] In April 2019, Hitachi ABB HVDC Technologies secured an HVDC guild for the Higashi Shimizu project to increase the interconnection capacity between the 60Hz area of Chubu Electric and the 50Hz area of TEPCO from 1.2GW to 3GW.[xi] Chubu Electric will increase the interconnection capacity of the Higashi Shimizu Substation from 300MW to 900MW which should be operational by 2027.[eleven] OCCTO (Organization for Cross-regional Coordination of Manual Operators) supervises the ability interchange among electric ability companies.[eleven]

Mode of product [edit]

| Year | Total | Coal | Gas | Oil | Nuclear | Hydro | Solar | Air current | Geothermal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | ane,121 | 294 | 26.2% | 256 | 22.9% | 169 | 15.0% | 282 | 25.ii% | 103 | 9.ii% | ||||||

| 2008 | 1,108 | 300 | 27.1% | 292 | 26.3% | 154 | 13.9% | 258 | 23.3% | 84 | vii.five% | ||||||

| 2009 | 1,075 | 290 | 27.0% | 302 | 28.1% | 98 | nine.1% | 280 | 26.0% | 84 | 7.8% | ||||||

| 2010 | 1,148 | 310 | 27.0% | 319 | 27.8% | 100 | eight.7% | 288 | 25.i% | 91 | 7.9% | iii.800 | 0.33% | three.962 | 0.35% | ii.647 | 0.23% |

| 2011 | ane,082 | 291 | 26.9% | 388 | 35.8% | 166 | 15.4% | 102 | ix.four% | 92 | viii.5% | v.160 | 0.48% | 4.559 | 0.42% | 2.676 | 0.25% |

| 2012 | 1,064 | 314 | 29.5% | 409 | 38.4% | 195 | xviii.3% | 16 | 1.5% | 84 | 7.nine% | 6.963 | 0.65% | 4.722 | 0.44% | 2.609 | 0.24% |

| 2013 | 1,066 | 349 | 32.7% | 408 | 38.2% | 160 | fifteen.0% | 9 | 0.nine% | 85 | eight.0% | fourteen.279 | 1.34% | 4.286 | 0.4% | 0.296 | 0.03% |

| 2014 | one,041 | 349 | 33.5% | 421 | 40.4% | 116 | 11.2% | 0 | 0% | 87 | 8.4% | 24.506 | two.35% | 5.038 | 0.48% | 2.577 | 0.25% |

| 2015 | 1,009 | 342 | 34.0% | 396 | 39.2% | 91 | 9.0% | 9 | 0.9% | 85 | 8.4% | 35.858 | iii.55% | 5.sixteen | 0.51% | ii.582 | 0.26% |

According to the International Energy Agency, Japanese gross product of electricity was 1,041 TWh in 2009, making it the world's third largest producer of electricity with 5.2% of the world's electricity.[24] [25] After Fukushima, Nihon imported an additional 10 one thousand thousand short tons of coal and liquefied natural gas imports rose 24% betwixt 2010 and 2012. In 2012 Nihon used most of its natural gas (64%) in the power sector.[26]

Nuclear power [edit]

Anti-Nuclear Power Plant Rally on 19 September 2011 at Meiji Shrine circuitous in Tokyo.

Nuclear power was a national strategic priority in Japan. Following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accidents, the national nuclear strategy is in doubt due to increasing public opposition to nuclear power. An energy white newspaper, canonical by the Japanese Cabinet in Oct 2011, reported that "public confidence in rubber of nuclear power was greatly damaged" by the Fukushima disaster, and it calls for a reduction in the nation's reliance on nuclear power.[29]

Post-obit the 2011 accident, many reactors were shut downwards for inspection and for upgrades to more stringent safety standards. By Oct 2011, only 11 nuclear power plants were operating in Japan,[30] [31] [32] and all 50 nuclear reactors were offline by 15 September 2013, leaving Nippon without nuclear energy for only the second fourth dimension in almost fifty years.[33] Carbon dioxide emissions from the electricity industry rose in 2012, reaching levels 39% more than than when the reactors were in operation.[34]

Sendai ane reactor was restarted on xi August 2015, the first reactor to meet new prophylactic standards and exist restarted subsequently the shutdown.[35] As of July 2018, there are nine reactors that take been restarted.[36]

Hydro ability [edit]

Hydroelectricity is Japan'due south main renewable energy source, with an installed capacity of about 27 GW, or sixteen% of the total generation capacity, of which about half is pumped-storage. The production was 73 TWh in 2010.[37] Equally of September 2011, Japan had 1,198 small hydropower plants with a total capacity of 3,225 MW. The smaller plants accounted for 6.vi percent of Nippon's total hydropower capacity. The remaining capacity was filled by big and medium hydropower stations, typically sited at large dams.

Other renewables [edit]

The Japanese government announced in May 2011 a goal of producing xx% of the nation's electricity from renewable sources, including solar, wind, and biomass, by the early 2020s.[38]

Citing the Fukushima nuclear disaster, environmental activists at a Un briefing urged bolder steps to tap renewable free energy so the world doesn't accept to cull between the dangers of nuclear power and the ravages of climatic change.[39]

Benjamin G. Sovacool has said that, with the benefit of hindsight, the Fukushima disaster was entirely avoidable in that Japan could take chosen to exploit the country'due south extensive renewable energy base. Japan has a total of "324 GW of achievable potential in the grade of onshore and offshore wind turbines | 222 GW| , geothermal power plants | 70 GW| , additional hydroelectric capacity | 26.v GW| , solar free energy | 4.8 GW| and agricultural residue | 1.1 GW| ."[40]

Ane consequence of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster could be renewed public back up for the commercialization of renewable energy technologies.[41] In Baronial 2011, the Japanese Government passed a beak to subsidize electricity from renewable energy sources. The legislation volition become effective on 1 July 2012, and require utilities to buy electricity generated by renewable sources including solar power, current of air power and geothermal free energy at above-market rates.[42]

As of September 2011[update], Japan plans to build a airplane pilot floating wind farm, with six 2-megawatt turbines, off the Fukushima coast.[43] Afterward the evaluation stage is consummate in 2016, "Nihon plans to build equally many every bit 80 floating wind turbines off Fukushima by 2020."[43]

Power stations [edit]

Grid storage [edit]

Japan relies more often than not on pumped storage hydroelectricity to balance need and supply. As of 2014, Japan has the largest pumped storage capacity in the earth, with over 27 GW.[44]

Run across as well [edit]

- Japan Electric Association

- Energy in Japan

References [edit]

- ^ "2016 Key World Energy Statistics" (PDF). www.iea.org. IEA. Retrieved ane Baronial 2016.

- ^ a b Energy in Sweden, Facts and figures, The Swedish Energy Agency, (in Swedish: Energiläget i siffror), Tabular array: Specific electricity product per inhabitant with breakup by power source (kWh/person), Source: IEA/OECD 2006 T23 Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2007 T25 Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Automobile, 2008 T26 Archived four July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2009 T25 Archived 20 January 2011 at the Wayback Motorcar and 2010 T49 Archived 16 October 2013 at the Wayback Car.

- ^ Nagata, Kazuaki, "Utilities have monopoly on power", Japan Times, 6 September 2011, p. three.

- ^ a b "Nihon electricity markets: structural changes and liberalization". Eurotechnology Japan. 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ "What does liberalization of the electricity market mean?". Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. METI. 2013. Retrieved i August 2016.

- ^ Stephen Stapczynski, Emi Urabe (28 March 2016). "Japan's Power Market place Opening Challenges Entrenched Players: Q&A". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ "Electricity market place shake-upwardly mainly benefiting Tokyo and Kansai". The Japan Times. 7 Apr 2016. Retrieved ane August 2016.

- ^ a b c "Japan's electricity deregulation not moving needle nonetheless". Nikkei Asian Review. four June 2016. Retrieved ane August 2016.

- ^ "The fraud called electricity retail liberalization". The Japan Times. 27 July 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Nihon'due south incompatible power grids". The Japan Times. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "ABB secures HDVC order for Higashi Shimizu project in Japan". NS Energy Business. 24 April 2019. Archived from the original on nineteen September 2021.

- ^ a b "Everything you need to know well-nigh the Japanese electricity grid". Shulman Advisory. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on twenty January 2021.

- ^ a b "A legacy from the 1800s leaves Tokyo facing blackouts". ITworld. xviii March 2011.

- ^ Gordenker, Alice, "Nihon'south incompatible ability grids", Nihon Times, nineteen July 2011, p. 9.

- ^ "Nippon – Assay overview". EIA. Retrieved fifteen April 2015.

- ^ "IEA – Report". world wide web.iea.org . Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "IEA – Written report". www.iea.org . Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "IEA – Written report". www.iea.org . Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "IEA – Report". www.iea.org . Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "IEA – Report". world wide web.iea.org . Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "IEA – Study". www.iea.org . Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "IEA – Report". www.iea.org . Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "IEA – Report". www.iea.org . Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ IEA Primal World Energy Statistics 2011, 2010, 2009 Archived vii October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 2006 Archived 12 Oct 2009 at the Wayback Machine IEA October, pages electricity 27 gas 13,25 fossil 25 nuclear 17

- ^ Bird, Winifred, "Powering Nippon's future", Nihon Times, 24 July 2011, p. 7.

- ^ "Nippon is the 2nd largest internet importer of fossil fuels in the globe - Today in Energy - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)".

- ^ Tomoko Yamazaki and Shunichi Ozasa (27 June 2011). "Fukushima Retiree Leads Anti-Nuclear Shareholders at Tepco Annual Meeting". Bloomberg.

- ^ Mari Saito (7 May 2011). "Japan anti-nuclear protesters rally subsequently PM call to close institute". Reuters.

- ^ Tsuyoshi Inajima and Yuji Okada (28 October 2011). "Nuclear Promotion Dropped in Nihon Energy Policy Later Fukushima". Bloomberg.

- ^ Stephanie Cooke (x Oct 2011). "After Fukushima, Does Nuclear Power Have a Future?". New York Times.

- ^ Antoni Slodkowski (15 June 2011). "Japan anti-nuclear protesters rally after quake". Reuters.

- ^ Hiroko Tabuchi (13 July 2011). "Japan Premier Wants Shift Away From Nuclear Power". New York Times.

- ^ Fukushima: Japan promises swift activeness on nuclear cleanup Prime minister Shinzo Abe makes pledge amid growing business organisation at scale and complication of operation The Guardian ii September 2013

- ^ http://www.globe-nuclear.org/info/Country-Profiles/Countries-Thou-N/Nihon/

- ^ "Restart of Sendai 1". Globe Nuclear Association. Globe Nuclear Association. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "Nippon'southward Nuclear Ability Plants". nippon.com . Retrieved thirteen November 2018.

- ^ Environmental impact assessment Country Analysis Briefs – Japan | 2012|

- ^ Bird, Winifred, "Distribution gridlock restricts renewables", Japan Times, 24 July 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Denis Gray (6 April 2011). "Activists telephone call for renewable energy at Un coming together". The Guardian.

- ^ Benjamin K. Sovacool | 2011| . Battling the Futurity of Nuclear Power: A Disquisitional Global Assessment of Atomic Energy, Globe Scientific, p. 287.

- ^ Justin McCurry (three May 2011). "Japan's nuclear energy debate: some meet spur for a renewable revolution". CSMonitor.

- ^ Chisaki Watanabe (26 Baronial 2011). "Japan Spurs Solar, Wind Energy With Subsidies, in Shift From Nuclear Power". Bloomberg.

- ^ a b "Nihon Plans Floating Air current Power Found". Breakbulk. 16 September 2011. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ Yang, Chi-Jen. "Pumped Hydroelectric Storage" (PDF). duke.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electricity_sector_in_Japan

0 Response to "Do Families in Japan Have Access to Electricity"

Post a Comment